Squatting, Citizenship, Ecology, Method: An Interview with Alex Vasudevan

Berlin's Prinzessinnengarten. (Source: https://www.stilinberlin.de/2012/06/food-in-berlin-prinzessinnengarten.html)

Alex Vasudevan is an Associate Professor in Human Geography at the University of Oxford, and an Official Student and Tutor of Christ Church, Oxford. His recent publications include The Autonomous City: A History of Urban Squatting (London: Verso, 2017), Metropolitan Preoccupations: The Spatial Politics of Squatting in Berlin (Oxford: Wiley-Blackwell, 2015), and (as co-editor) Geographies of Forced Eviction: Dispossession, Violence, Insecurity (London: Palgrave, 2017).

He is responding here to a set of questions developed by William Conroy, based on his work. William completed his MPhil at Oxford in 2018, and studies urban political ecology, racial capitalism, and the commons. (This interview transcript has been edited for clarity and brevity.)

Squatting and Citizenship

WC: In some of your writing, you have noted that squatting can play a role in the articulation of insurgent citizenship claims. How, if at all, do squatters complicate the notion of citizenship as a “juridical relation”?

AV: One of the points of reference for thinking about insurgent citizenship in my work, unsurprisingly, is James Holston’s work in Brazil, which helps us to complicate the distinction between formality and informality. He explores the often illegal practices adopted by informal settlers, which in many cases are driven by a desire to formalize a relationship with the state. Still, much of my work is located in the Global North, and I have probably spent less time thinking about the question of insurgent citizenship in recent years. I suspect this is a product – or perhaps a consequence – of the kinds of struggles I have been working through. That being said, I think there is important work still to be done in the context o the Global North. Scholars whose work is embedded predominantly in that context would benefit from learning lessons from their counterparts in the South.

I’m thinking especially of squatting movements and their relationship to migrant struggles in Southern Europe. Those struggles often operate in a liminal or grey space, where questions of citizenship and the law actually assume a critical urgency. So, where I would, if I had time, think about those issues is in that very space. I would also add that there is far more work to be done on the relationship between the law and urban squatting, partly in response to the growing criminalization of squatting across Europe and North America.

WC: You have described squatting in the past through the lexicon of infrastructure – that is, as a “genre of urban infrastructure” (Vasudevan, 2017) that entails translocal and contingent “relations between bodies, spaces, and materials” (cf. McFarlane and Vasudevan, 2014). Could you speak more on the significance of understanding squatting as infrastructural? In what sense is that framing politically significant?

AV: I think one of the things I am really interested in is understanding what squatters actually do – the practices they mobilize and the kinds of spaces they create. In some of my historical work, I have been struck by the infrastructures and networks that squatters were successful in producing, be that in West Berlin and Amsterdam in the early 1980s or in the East Village of New York. It struck me that the act of squatting – the act of occupying a particular vacant property or plot of land – wasn't the end point in thinking about what was going on in those and many other cases. Squatters were often involved in creating not only a space – or re-functioning a particular space – but were also often involved in trying to make connections between different practices, between bodies and space, between different understandings of architecture. I thought, and continue to think, that the term “infrastructure” was a useful point of reference, or a kind of conceptual placeholder for understanding what they were trying to do.

This type of infrastructural agenda was something that squatters were very open about articulating. They often saw their actions as a tool in a broader struggle around housing insecurity, and understood that those struggles didn't end in the act of occupation, but actually only began, in many ways, with occupation. A lot of the existing work about infrastructure within urban studies has operated in rather different contexts and with a rather different set of politics in mind. I think that the kind of practices, tactics, and makeshift knowledges that I have been involved in tracing enroll a different sense of the importance of infrastructure. Furthermore – and this is something I haven’t thought about – I think there certainly are citizenship-based claims that often attach themselves to this type of infrastructural production. We have seen this in the context of work in hydro-politics. But I think there are perhaps other ways of thinking about precisely that intersection between infrastructure and citizenship, not least in the context of squatting.

“Squatters were often involved in creating not only a space – or re-functioning a particular space – but were also often involved in trying to make connections between different practices”

WC: To your mind, what is the role of the built form – and materiality more generally – in the production of “new forms of collective living” (Kunst and KulturCentrum Kreuzberg, 1984 quoted in Vasudevan, 2011)? How does the built form, and materiality, relate to the affective geographies of squatting, and to squatters’ attempts to transcend “particular conditionings of the individual and the self” (Heyden, 2008 quoted in Vasudevan, 2014)?

AV: Simply put, one of the things I’ve learned in my research is not to treat squatted spaces as containers for particular political forms, but actually to think about the relationship between those spaces and the kinds of political processes they produce. It's a two way process. In many cases the built form may activate certain kinds of politics; in others, a particular politics transforms the built form.

If we track the history of urban squatting – thinking again about the work I’ve been doing in Europe and North America from the late 60s onwards – the role of architecture and planning in that story is significant. Many squatters were planners or architects themselves. In some cases their impulses were preservationist: they were interested in restoring housing stock that would otherwise disappear in the context of “regeneration” and “urban renewal.”

But many of them were also interested in treating architecture as an opportunity – as a catalyst for creating different kinds of political alliances and identities. For them architecture could be actively refashioned for the sake of politics. The built form of particular squatted spaces provided an opportunity – a source for different ways of organizing relationships. Therefore, in many cases squatters quite actively transformed the spaces they occupied. There was a really active sense of refashioning space, a kind of “DIY empiricism” – and experimentalism – that involved repurposing the built form with an acute awareness of what the built form could do.

I also use the phrase “makeshift urbanism” in this context, and it has been taken up in other ways by other scholars to try to convey and conjure a sense of both that spatial experimentation, and also the precarious nature of that kind of incremental transformation of urban space. I would add that there is a danger here that we romanticize that process. Many of the spatial tactics adopted by squatters were mobilized in settings of extreme inequality, and also in contexts where the threat of eviction and general housing insecurity was the main horizon of experience; the very act of transforming a space was one shaped by questions of survival and endurance.

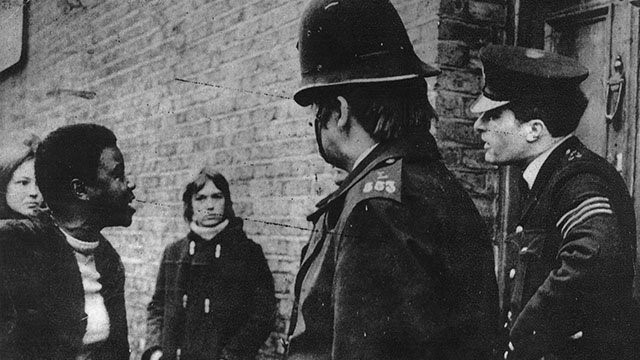

Eviction Resistance, Brixton, 1999. (Source: https://www.radionz.co.nz/national/programmes/nights/audio/201840051/squatting-and-the-era-of-housing-activism)

Spatio-temporality

WC: How do you understand “cityness,” and in what sense is the notion of cityness – if at all – “constitutively political” (cf. McFarlane and Vasudevan, 2014)?

AV: One of my points of reference for thinking about cityness is the work of AbdouMaliq Simone. That said, I am concerned with the kinds of practices and tactics that informal settlers in the Global South and North have mobilized, and how they were – and are – attentive to what Simone would describe as cityness [attentive to the constant becoming and transformation of the city]. I think there is an understanding of cityness that’s intrinsic to the kinds of politics and practices that squatters are interested in. Elsewhere I have described squatters as radical custodians of cities; in some sense the city that they try to re-configure and assemble is built on an archive of practices and knowledges as well. I guess when I talk about cityness I’m really interested in the kind of “structure of feeling” that these kinds of practices produce, as well as recognizing that this structure has a material form as well.

WC: You have described “autonomous urbanisms” in which particular ideas about “times and spaces” were developed; you have also called attention to the anticipatory logics embedded within the “trope” of occupation (see Vasudevan, 2015a). Is there a particular spatial and/or temporal epistemology – or, perhaps, ontology – that propels practices of urban commoning?

AV: That’s a big question. First, I think there are a couple ways we can think about urban commoning. I tend to come at it by considering how the drive to produce urban commons is immanent to certain struggles within cities. Second, I’ve probably shied away from thinking through some of the bigger claims that this question is probing. My basic interest is really in trying to understand the conditions of possibility – if you like – for producing “other” kinds of urban politics, ones that are autonomous in that they exist outside of the constraints imposed by the state. There are many people who would argue, if they were putting a Foucauldian hat on, that various constraints always limit what constitutes autonomy. But in my view I think there still is some purchase – some value – in trying to think through the notion of autonomy and the urban commons. I’m probably inspired, in this sense, by debates and struggles that emerged in particular out of Italy in the 60s and 70s under the umbrella term “autonomia.”

I realize I’m skirting around your question, perhaps. It’s not one I’ve thought about – this idea of space-times – but from my point of view I am really quite interested in re-asserting the urgency of the question of autonomy in urban politics; in sketching out a horizon of urban possibility. This is especially urgent in a context in which those who are making claims to the “right to the city” are often not doing so on behalf of the commons, but on behalf of far more revanchist forms of the political. We have seen struggles over the right to the city being mendaciously mobilized by the far right in particular – as they try to parasitically use the language of rights-based discourse. And so I think the question of aligning autonomy with the commons is more urgent than ever.

The Autonomous City: A History of Urban Squatting. (Source: https://www.versobooks.com/books/2435-the-autonomous-city)

WC: You have referred to the colonization of everyday life as “globalization turned inward” (see RETORT, 2005, quoted in Jeffrey et al., 2007). What does that mean?

AV: In thinking on the question of the colonization of everyday life, the point of reference, the touchstone, is Debord. I have also spent quite a bit of time reading, and working through some of the ideas put forward by the RETORT collective as well, and they drew heavily on Debord.

Rather than solely track the different translocal scalar politics that we often associate with globalization, why not look at it from the other way around? Why not attend to the ways in which the wage relation and the question of value are imposed on people’s lives in ways that they never have before? These forces enter into the very fabric of everything we do. And obviously this has taken on new forms when one considers the really important work being done now on algorithmic governmentality which, if anything, has further weaponized these logics of value making – of extraction. It is important to attend to the sheer scale of these processes. There may still be some kind of outside, but that seems precariously poised at a horizon that is receding from view.

Obviously the word colonization also – and this is equally important – implies a particular set of practices, and I think the use of that term needs to be developed with greater precision and acuity as well. We need to place work on the colonization of everyday life in conversation with the literature on decolonization and settler colonialism. This would open up not only conceptual possibilities, but methodological ones as well.

Commons-enclosure

WC: You have written on the “capture” and instrumentalization of occupation-based practices for the sake of “neoliberal urban renewal” (Vasudevan, 2015a). How, then, do you understand the function of squatting in the context of a “‘crisis’ urbanism” (Brickell et al., 2017) that seeks to strengthen the “intimate connection between the development of capitalism and urbanization” (Harvey, 2008, quoted in Vasudevan, 2014)? How can practices of urban occupation function, if at all, as value-creating activities that are “not subsumable to or simple expressions of capital” (Vasudevan, 2011)?

AV: This is one of the really important aspects of trying to understand struggles around housing and urban squatting, especially in Europe and North America. In that context – as a number of people have quite rightly pointed out – those practices have very routinely been coopted and captured by, broadly defined, the logics of capital, and have been subsumed in a whole host of processes of new liberal urban regeneration. In one sense squatters face a double bind – the very logics they resist often give them a kind of “line of flight” to survive in ways they otherwise wouldn't.

Historically, this has meant that the specific spaces they occupied have often persisted in some form, but at the expense of the larger neighborhoods in which they were embedded. There was always this kind of paradoxical tension as squatters found themselves complicit in the very processes that they were contesting. It’s important also to acknowledge that many activists and squatters were, in fact, actively involved in those logics of regeneration and gentrification as well. Some were perfectly relaxed about gentrification.

It is in this kind of context that one wonders whether you can still see squatting as an “other” to creative destruction. However, I think there are all sorts of ways in which squatting might generate other forms of value that are not subsumable to the logics of capital. Here, the relationship between squatting and property is important, and it’s a story that still needs to be told in greater depth. Take the Lower East Side of New York. There, many properties were actually sold to squatters – they were meant to bring them up to code using sweat equity – which lead to a particular kind of possessivism.

The question we might want to ask ourselves is: are there ways to assert other kinds of propertied relations that escape this type of possessivism? I think that would be incredibly difficult in the current conjuncture, given that the possibilities for generating alternatives right now are far more limited than they were even 10 years ago, and obviously 20 or 30 years ago – that's a very different world. That being said, there are also new horizons coming into view.

Moreover, a lot of work in Southern Europe around the “migrant crisis,” if you want to call it that, has opened up new forms of experimentation with collective living. I think those experiments may at least suggest what a different kind of urban commons might look like – one that isn’t subsumable by forms of urban renewal. Still, I’m probably relatively pessimistic. It does feel like a particular period of urban activism is coming to an end. Given the growing criminalization of squatting, for example, the room for maneuver has been profoundly circumscribed.

WC: How does race – and racialization – function in your theoretical understanding of the commons-enclosure dialectic?

AV: It doesn't enough, and this is a blind spot in my work that I’m trying to respond to; urban studies still has a long way to go in understanding and taking seriously questions of race. Obviously there are a number of people who have made that argument far more eloquently and powerfully than I can, including people like Ananya Roy (and many others), who I think has tried to re-center what it means to do urban studies. What is interesting is, for example, the recent application of debates in abolitionist political ecology to planning and architecture. There is so much more we can learn here.

When one thinks about particular histories of urban politics and urban struggle – including squatting – the question of race is always there. It’s something that I talk about certainly in The Autonomous City, but not enough. In that work, I discuss struggles around housing insecurity in London, and actions undertaken by the British Black Panthers, including people like Olive Morris. I also discuss, for example, Operation Move-In, which was a very important series of squatter-based actions in the Upper West Side – to begin with at least – in New York in the late 60s, early 70s.

Those actions were largely undertaken by working class Puerto Rican women, but that story is often written out of the more “heroic” narratives around housing struggle in New York. And yet, it's a really important part of the history. So I guess what I am trying to say is that, if we are going to think through logics of racialization in the context of particular historical processes, we also need to take seriously – in the first instance – who were in fact the subjects of historical struggles around these processes. In many cases, those struggles have been whitewashed. And, this is not only about how we theorize – this is an empirical question as well.

Olive Morris. (Source: https://libcom.org/history/morris-olive-elaine-1952-1979)

Method

WC: Does your interest in historical geography, and the urban archive, have a political impulse? Further still, do you understand this methodological approach [archive-based historical geography] as entailing the production of constellations, or dialectical images, in the Benjaminian sense?

AV: I’ll take the first part of the question first. As I’ve said, squatters are often radical custodians of the city. They maintain an intimate understanding and knowledge of the city. They carry with them a particular kind of archive as habitus. Related to that, squatters often assemble their own archives. Historically, they have created a meticulous and detailed archive in response to what they understood as mainstream misrepresentation. Wherever you travel in the context of the history of squatting you encounter these makeshift, assembled archives.

In some cases they have been institutionalized, so a lot of the materials that we associate with the Lower East Side in New York are now located in the Tamiment Library at NYU. Similarly, many of the archives associated with squatting in Denmark are now in the National Archive. But obviously, many of these archives also remain in quite precarious and makeshift spaces that have been created and curated by local activists. With that said, I’m really interested in how the archive – and the process of archiving – is another way of doing urban geography, or doing urban studies. There is a presentism in a lot of urban studies that ignores the importance of the historical record, and I think we can learn a lot from these archives.

Now, the second part of the question is to what extent we can or should juxtapose that historical record with our current constellation of urban practices. I think the Benjaminian term – one that I briefly allude to in Metropolitan Preoccupations – is one that would benefit from being developed in greater detail. The Benjaminian impulse is a methodological one. It’s about the way in which we present our work and how we work through particular problems. I think its important to read the history of activist practices in those terms. This method also allows us to avoid highly romanticized hagiographies of activism, which see a continuity between practices that date back to the 60s in the present, without making sense of all the disjunctures, the erasures, the occlusions embedded in those accounts.

WC: How has your early work on visual art and aesthetic theory – for example, your writing on the “rematerialization of the aesthetic object” (Vasudevan, 2007) – informed your work in urban geography and radical urban social movements?

AV: In many ways. I’m trained as a historical and cultural geographer in the first instance, and my PhD was predominantly preoccupied with trying to understand the performance cultures that played a central role in the making of Weimar Berlin. With that project, the question of the aesthetic assumed a certain centrality, and such questions have never really disappeared. I am certainly still interested in the points of intersection between aesthetics and politics in all sorts of ways; those are very urgent questions when we consider how aesthetics and politics can be configured for very reactionary ends.

Needless to say, I am interested in the precise opposite – the way in which we can think about putting the aesthetic and political into a radically progressive constellation. The earlier question about Benjamin is a very important one in that context. Weaving through my work is an enduring concern with those kinds of issues and an attentiveness to the notion of squatting as making or fabulation. This attentiveness recognizes that in many cases squatters were themselves artists, they were involved in artistic communities, and they often instantiated new kinds of aesthetic practices within particular “scenes.”

So I don’t think my concern with the aesthetic has ever receded from view; however, the way in which I pose that question has changed considerably since my PhD and some of my earlier work. For example, I have recently been struck by conversations with the artist Tom Burrows, who was also a squatter for many years on the Maplewood Mudflats on the North Shore in Vancouver. He approached the very act of squatting in terms that were quite close to what Joseph Beuys would refer to as “social sculpture.” The kinds of questions he asked in his practice as an artist were closely intertwined with the environment in which he was living.

Ecology and Ontology

WC: You teach a course on “urban natures” and urban political ecology. In what sense can squatting be understood as an ecological practice?

AV: I’ve come rather late to urban political ecology; that was more serendipity than anything else. I have always been familiar with it at a distance, but more recently – in teaching the course you mentioned – I do wish I had come to political ecology earlier on. There are some very interesting squatting initiatives that frame themselves in overtly ecological terms. The kinds of projects we see in Spain for example, where you have activists in Catalonia squatting a village that’s been abandoned, working to create a sustainable community out of quite literally a ruin, and adopting a whole range of “ecological sensibilities” in re-functioning that space.

That being said, I think there is another way in which we can think about the ecological impulse of squatting more broadly – so as to recognize that this impulse is perhaps embedded in the kind of makeshift ethos adopted by a lot of squatters. I’ll be careful how I frame this, but squatters generally have a certain sensitivity to the production and maintenance of urban natures. Historically, squatters were often involved in projects like Berlin’s Prinzessinnengarten.

That is a community garden that was reclaimed by activists in recent years, and which otherwise would have been transformed, inevitably, into some kind of luxury development. And the relationship is not simply one-sided. Political ecological sensibilities in Berlin parallel in many ways the emergence of radical housing initiatives in the city. Matt Gandy’s recent documentary film – and his written work on this subject – I think requires further reading and thinking through, but it does suggest these various points of intersection and points of conversation between squatting and a type of urban environmentalism.

There are a number of other examples. For instance, one might be surprised to learn that MORUS – the Museum of Reclaimed Urban Space, which is in the Lower East Side – narrates two stories. One is obviously the history of squatting in the neighborhood, but the other is the history of community gardening. In that case, too, we find a radical ecological sensibility threaded through the history of urban squatting.

Berlin's Prinzessinnengarten. (Source: https://www.stilinberlin.de/2012/06/food-in-berlin-prinzessinnengarten.html)

WC: In what sense does a “modest ontology of mending and repair” (Vasudevan, 2015b) inform the politics of squatting?

AV: I am very interested in squatting as making, as craft, as a kind of building, an active process. In my research I am often struck by the work it takes to rehabilitate and re-function a space. Moreover, the notion of a “modest ontology” is a nod to the fact that squatters are often able, quite successfully, to mobilize and produce a different sense of what it means to live in a city.

Alex Vasudevan is an Associate Professor in Human Geography at the University of Oxford, and an Official Student and Tutor of Christ Church, Oxford. His recent publications include The Autonomous City: A History of Urban Squatting (London: Verso, 2017), Metropolitan Preoccupations: The Spatial Politics of Squatting in Berlin (Oxford: Wiley-Blackwell, 2015), and (as co-editor) Geographies of Forced Eviction: Dispossession, Violence, Insecurity (London: Palgrave, 2017).

William Conroy completed his MPhil at Oxford in 2018, and studies urban political ecology, racial capitalism, and the commons.

Works Cited

Brickell K, Fernández Arrigoitia M and Vasudevan A (2017) Geographies of forced eviction: dispossession, violence, resistance. In: Brickell K, Fernández Arrigoitia M and Vasudevan A (eds) Geographies of Forced Eviction: Dispossession, Violence, Resistance. London: Palgrave, pp. 1-24.

Jeffrey A, McFarlane C and Vasudevan A (2007) Spectacle, state, modernity: a commentary on Retort’s Afflicted Powers. Geopolitics 12: 206-222.

McFarlane C and Vasudevan A (2014) Informal infrastructures. In: Adey P, Bissell D, Hannam K, Merriman P and Sheller M (eds) The Routledge Handbook of Mobilities. New York: Routledge, pp. 256-264.

Vasudevan A (2007) ‘The photographer of modern life’: Jeff Wall’s photographic materialism. cultural geographies 14: 563-588.

Vasudevan A (2011) Dramaturgies of dissent: the spatial politics of squatting in Berlin, 1968-. Social & Cultural Geography 12(3) 283-303.

Vasudevan A (2017) Squatting the city: on developing alternatives to mainstream forms of urban regeneration. Available at: https://www.architectural-review.com/essays/squatting-the-city-on-developing-alternatives-to-mainstream-forms-of-urban-regeneration/10021291.article (accessed 6 March 2019).

Vasudevan A (2014) Autonomous urbanisms and the right to the city: the spatial politics of squatting in Berlin, 1968-2012. In: Van Der Steen B, Katzeff A and Van Hoogenhuijze L (eds) The City is Ours: Squatting and Autonomous Movements in Europe from the 1970s to the Present. Oakland: PM Press, pp. 131-152.

Vasudevan A (2015a) The autonomous city: towards a critical geography of occupation. Progress in Human Geography 39(3): 316-337.

Vasudevan A (2015b) The makeshift city: towards a global geography of squatting. Progress in Human Geography 39(3): 338-359.